I am delighted to present this article on the really important topic of ‘Sudden Vision Loss’ on the Optometry-Evolution website. This has been brought to you with the very kind support of ‘Optelec.’

I am delighted to present this article on the really important topic of ‘Sudden Vision Loss’ on the Optometry-Evolution website. This has been brought to you with the very kind support of ‘Optelec.’

This is the first ever guest-written article on the site and has been authored by colleague of mine Dr David Roberts, who was previously an optometrist, who then studied medicine and trained in ophthalmology, so an excellent person to give us this review in a way which is really useful to us as optometrists.

Sudden visual loss

Experienced practitioners will have learnt that cases of sudden visual loss will often present at an inconvenient time – no doubt due to the anxiety the symptoms generate in the patient. This leads them to seek immediate advice whenever that may be. Therefore wherever possible provision should be made within your practice for these patients to access emergency appointments. This article aims to review the common causes of sudden visual loss and to provide guidance on their management.

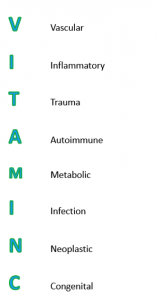

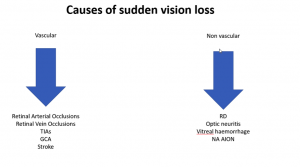

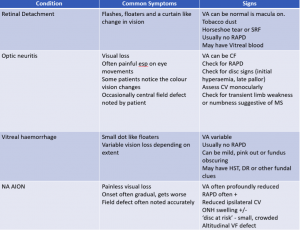

It is always important to have a logical framework when considering the potential causes of a presentation, such as one of the `Surgical Sieves.’ In particular, the causes of sudden visual loss are often categorised as those due of vascular origin and those which are not. Vascular causes are common and include transient ischaemic attacks, strokes, arterial and venous occlusions. Non-vascular causes could be due to retinal detachments or trauma.

Case History

In general, the key to an effective consultation is the ability of the practitioner to unify the patient`s subjective symptoms with the examiner`s objective findings into a formulation and plan of action. So a careful history needs to be elicited which could include the following questions (but is not limited to them!):

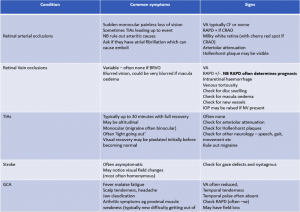

Patient age Most causes of sudden vision loss are more common with advancing years.

General medical status Are there any risk factors for a vascular cause such as diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol? How stable is the condition? Are there any contributing lifestyle factors such as smoking or nutritional causes such as excessive alcohol intake?

Is one eye or both affected? Most cases will be unilateral. In cases of stroke or advanced GCA there may be bilateral symptoms.

What was the patient doing when they noticed it? How long ago? The length of duration of symptoms is important in deciding the management. Sometimes the mechanism of how the symptoms came about gives you a clue to the cause.

Is the visual loss absolute or relative? CRAO tends to affect the whole field of vision while BRAOs are often described by the patient in a way that matches the pathology.

Does it affect the whole field of vision or a part of it? If partial – which part of vision is it?

Are there any other symptoms, such as pain or features of stroke? Optic neuritis and GCA could be painful, most other causes are painless

Has the change been transient or permanent? Is it getting better or worse? TIAs will often present as normal or near normal by the time you see them so a history is important.

Is there any ocular or medical history which might be relevant? For example, a history of trauma which could increase risk of retinal detachment.

The Clinical Examination

A careful history will usually provide a good differential diagnosis for you to proceed with, and in some cases will give you the diagnosis itself! The next step in assessment is to examine the patient with the aim of evaluating if your theories regarding the cause are correct or not.

A framework for assessment could include the following:

Visual acuity – always assess this first.

Pupils – especially RAPD. Assessing for a RAPD is a short test but has significant implications. For example a retinal vein occlusion with a RAPD is likely to be ischaemic, carries a worse prognosis and is more likely to need laser and IVT.

Visual fields to confrontation Automated fields might be indicated as well

Motility – to assess for neurological deficits which may be associated.

Anterior segment assessment and IOP

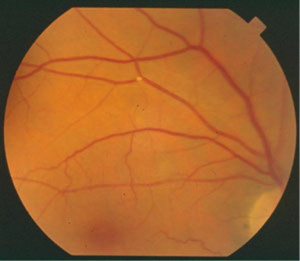

Dilated posterior segment evaluation -for a general dilation tropicamide 0.5% may be sufficient but it is advisable to optimise your dilation with one or more agents if sinister pathology is expected.

Case management

By this stage you will probably have a good idea of what the cause of the visual loss is. The patient will usually need to be referred onwards, usually to the ophthalmology department but sometimes to the GP in the first instance.

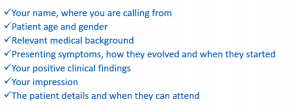

When referring, make sure you tell the doctor or triage nurse your name, where you are calling from, and the patient`s name and age, then a concise summary of the history and findings with an impression of what you think is going on. A clear and repeatable delivery of information will impress the person receiving the referral so that it won`t matter if you`re not 100% clear on the diagnosis. The importance of a clear delivery of information cannot be under-estimated.

Do consider following up with the patient or doctor about what happened downstream of your assessment – this will not only complete your learning cycle but will demonstrate your commitment to your patient and will help to promote your good standing with them.

It is difficult to deliver an exhaustive guide to sudden loss of vision in the scope of one article, however hopefully this is gives some clinical nuggets as how to approach these cases.

Dr David Roberts – About the author. Dr Roberts was an optometrist working in Scotland, before studying medicine in St Andrews and doing subsequent ophthalmology training in Dundee. He has an ongoing interest in education and is now a medical reviewer for Staar in Switzerland.