It’s hard to believe that we are well into 2019 and once again hitting hayfever season. At last winter is behind us, we have longer days, warmer weather, the natural world around us waking up and growing once again, however for our seasonal allergic conjunctivitis sufferers, this is not all welcome news.

I very recently delivered a webinar on this topic and thought it would be a great time to share this as an article given the season. In this, I will explore the main mechanism and causes of allergy, how it allergy manifests itself in eyes, and importantly how we as optometrists can play our role in helping these patients.

This can either be viewed as an online lecture by following this link, or by reading the article below.

The extent of allergy as a public healthy problem is vast. It is thought that around 44% of individuals in the UK suffer from some form of allergy. Children suffering from hayfever and other common forms of allergy have trebled in the past 30years. The cost to the NHS each year is thought to be in the region of £900milion in terms of treating allergies, plus the other socio-economic costs from days off work for example.

Various studies have looked the prevalence of ocular allergy, and this appears to fall in the range of 10-20% of the general population, with most of these being Seasonal or Perrenial Allergic Conjunctivitis sufferers. One study by Wolffsohn equated this to each full-time optometrist seeing approximately 225 ocular allergy patients in practice each year. Ironically these are not presentations I see many of as I work in hospital so this is testament to the work that goes on in primary settings such as optometry and pharmacy practices in helping these patients.

What is allergy? Well, allergy covers a wide range of conditions whereby we see the immune system becoming hypersensitive to some material in that we come into contact with or ingest, producing an exaggerated immune response. The immune system is intended to deal with these allergens in a safe and controlled fashion, however in this exaggerated response we develop unwanted signs and symptoms and possible damage to surrounding tissues as a result. The range of conditions encompasses milder nuisance conditions such as hayfever to life threatening conditions such as anaphylactic shock. In relation to the eye again there is a range of presentations from the milder Seasonal or Perrenial cases to more serious conditions such as Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis and Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis which can be sight and eye threatening.

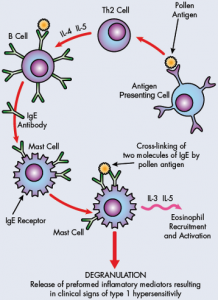

Allergy is driven by a hypersensitivity reaction, of which there are 4 main types. These can be complex to follow, and thankfully for the scope of this article we will just concentrate on Type 1 hypersensitivity as this the mechanism for most of our ocular patients.

This reaction alters the activity of our mast cells, which are really the containers for a lot of our inflammatory response mediators. When we are exposed to a certain allergen, e.g. grass pollen, this can bind to our B-cells, which help set up the production of IgE antibodies which are specific to this grass pollen. These IgE antibodies bind to the wall of the mast cells, so they are now sensitized to this pollen allergen. With subsequent exposure to this same allergen, this can bind to the IgE’s on the mast cells, in turn causing the mast cell to degranulate, or basically open the gates for all of the inflammatory mediators to release and start to make their effects known. These mediators can produce a variety of changes. Blood vessels dilate, becoming more visible and permeable for fluid leakage. Nerve endings become stimulated to cause itching sensation. This is the first phase of the reaction – the second phase is when other cells are attracted to the site such as eosinophils which augment the inflammatory reaction and increase histamine.

Histamine is one of the key mediators in such a response and once it is released, it causes a variety of changes. Mainly vasodilation, so redness increases, increased blood vessel permeability leading to swelling and nerve stimulation leading to itching sensation.

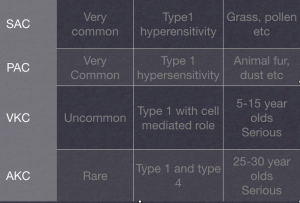

Moving on to the eye more specifically – such allergic responses can bring about Allergic Conjunctivitis in one of its four main forms. The two most common are Seasonal Allergic Conjunctivitis (SAC) and Perennial Allergic Conjunctivitis (PAC) which are also the least harmful for the eye. The second two conditions, Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) and Atopic Keratoconjunctivitis (AKC) which are much less common but potentially much more serious.

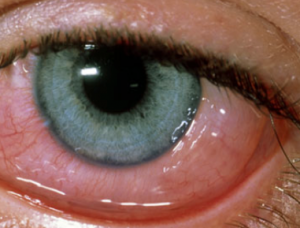

SAC and PAC share the same clinical presentation essentially, with the main difference being in the underlying material or allergen causing the reaction. Seasonal cases are so-called as the allergen will be an environmental substance such as pollen from grass, trees and crops for example, whereby the allergen in PAC will be a material which is around all year round such as animal fur, dustmites etc.

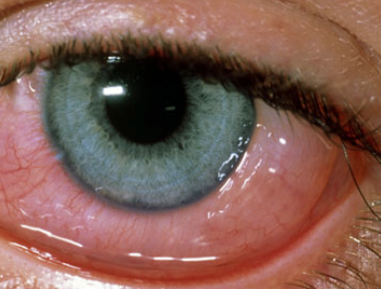

These cases present with bilateral injected, watering, itching eyes. The conjunctiva can become chemotic and the lids swollen. If you evert the lids papillae may be visible.

These are small vascular abnormalities with a surrounding area of fluid and inflammatory cell infiltrate. The features that help with differential diagnosis are the bilaterality of the condition, the presence of papillae, itching sensation and watering. Often the patient will have a history of this condition or other manifestations of allergy.

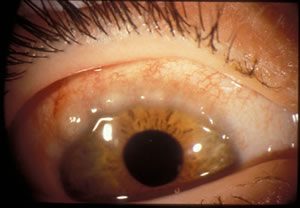

VKC has a slightly more severe presentation. The patient is often very uncomfortable and photophobic. This conditions affects younger patients from the age of 5-15, with a preponderance towards males. This condition occurs more readily in hot, dry climates and around 80% of patients will have a background of atopy.

The other features making this distinct from SAC and PAC is the thick discharge, occurrence of giant papillae and limbal changes such as Trantas spots which are raised white lesions full of dead epithelial cells and other inflammatory debris. These are significant as they can lead to keratitis resulting in damage to the vision and the eye itself.

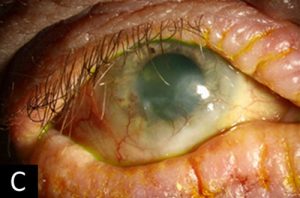

Finally AKC is another of these two more serious conditions. This affects adults in the age range of around 25-35. Again they present with redness, itching and photophobia. The feature that makes this condition stand out is that there are often blepharitic lid changes due to eczema caused by the underlying atopy.

These patients can also develop keratitis and run a risk of microbial ulcer due to staphylococcal lid disease. Once again these patients are at risk of developing keratitis which can ultimately put the vision and the integrity of the cornea, so really needs specialist investigation and management.

Management of Allergic Conjunctivitis (SAC and PAC)

Before discussing the pharmacological options available to us, there are quite a few simple non-medicinal measure we can take which may improve the signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis.

Firstly, if it is possible to identify the allergen that can really helping terms of removing or minimising contact with this. Skin-prick testing can sometimes help with this.

The following is a list of measures we can think about which may also help:

- Avoid eye rubbing. This can cause mechanical release of histamine and other mediators.

- Good hand and hair hygiene. If you have been in an environment with the allergen, e.g. in pollen, wash your hair before going to bed to reduce the exposure to the allergen.

- Domestic hygiene measures – hoovering, dusting and regular cleaning of bed linen, particularly in cases of PAC.

- Daily disposable contact lens wear – some studies have shown that these reduce signs and symptoms by limiting ocular surface exposure to the allergen.

- Cold compress – causes vaso-constriction to reduce redness and symptoms.

- Artificial tears – dilutes and removes the allergen load on the ocular surface.

- Close fitting sunglasses – limit the exposure of the ocular surface to allergens when outside.

These measures may not be suitable or appropriate in every case but certainly really useful to keep in mind, as they may be sufficient in milder cases, and avoid the use of medications.

These measures may not be suitable or appropriate in every case but certainly really useful to keep in mind, as they may be sufficient in milder cases, and avoid the use of medications.

If pharmacological drops are required, there are a few different classes of agents available to us. The choice of drops will depend on various factors – the type and severity of disease, whether you are treating acute symptoms or aiming to prevent seasonal onset of this disease, and also perhaps your prescribing status as an optometrist, as some of these require AS or IP.

Decongestants

These are sympathomimetic amine agents which bring about a temporary narrowing of blood vessels, which reduces injection. The main agent used in this regard is Naphazoline which is a ‘P’ medicine. Mainly used in mild cases however the drops themselves may cause some ocular irritation.

Topical Antishitamine

Antihistamines work by blocking H1 receptors which histamine would normally bind to in order to bring about its various effects. These can be used in different modes including oral or topical eyedrops, which is what we will look at first.

Topical antihistamines tend to be the main drop choice in terms of relieving acute allergic symptoms. In cases where the patient has had a reaction, and is displaying the signs and symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis, these can be effective at reducing the clinical features. Most products are ‘P’ medicines so can be used by all optometrists, however if they are used in combination with a mast cell stabiliser they may be a ‘PoM’ product. There is also some variance in terms of the age from which these agents can be used, with some not recommended for patients under 12years old. It is always worth checking product information in the BNF, manufacturers leaflet and the optometrists’ formulary.

There are some anti-histamines which can be used in younger children such as Azelastine and Ketotifen which can be used from the age of 4 and 3 respectively. They are both PoM products, which is worth noting.

The combinations that are available include an anti-histamine combined with a decongestant e.g. Otrivin Antistan . This is a ‘P’ medicine however can only be used in children above the age of 12 and should be avoided in pregnancy and patients with pulmonary problems.

Combinations with mast cells stabilisers are also used such as Olapatadine (PoM.) This is a useful option as it can be used in children from the age of 3, and used for longer periods of up to 4 months.

Oral Antihistamines

This group of medicines can be a useful option if the patient is suffering nasal and throat symptoms as well as ocular manifestations. These are available in a variety of modalities such as tablets, syrups and nasal sprays. These are ‘P’ medicines so these can be provided by an optometrist. These can be used in conjunction with topical ocular treatments. It is again worth being familiar with these products as there may be age restrictions and possible side effects such as drowsiness with their use. The advice of pharmacy colleagues who are using these products regularly might be a helpful option.

Topical Mast Cell Stabilisers

This group of drugs works in a different mode to anti-histamines. As the name suggests these try to stabilise the mast cells so that degranulation and release of all the inflammatory mediators is blocked. These aren’t as useful in gaining a quick response to an acute allergic response as they have no effect on histamine that has already been released. The main area where these are useful is in individuals who have seasonal disease and aim to pre-empt this by taking MCS’s prophylactically. These can take up to 10-14 days to take effect.

MCS’s are often used in combination with anti-histamines so that you get the benefit of the acute relief of symptoms brought about by the antihistamines, and the ongoing suppression of the mast cells.

These preperations also differ from anti-histamines in that they are PoM products requiring either ‘additional supply’ or ‘independent prescribing’ status.

Common examples include sodium cromoglygate, nedocromil and lodoxamide. The latter two agents tend to be more potent and are used in more serious cases such as VKC.

Topical NSAIDS

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be another option in cases of SAC and PAC. These work in a different mode of action in that they block prostaglandin formation which is one of the main inflammatory mediators. Care needs to be taken to ensure there is no underlying ocular infection particularly of the cornea as these could allow for this to develop more rapidly.

As PoM medicines optometrists need to be additional suppliers or independent prescribers in order to use them, and it should be noted that they aren’t recommended for paediatric use.

Topical cortico-steroids

Steroids are not routinely used in allergic eye disease but can be used in their various strengths in certain situations. Less potent forms may be considered in severe cases of SAC or PAC, while stronger version may be required in more serious conditions such as VKC and AKC. All of these drugs are PoM and require Independent prescribing status, given the higher risk of side effects associated with these drugs.

Milder preparations may be considered in more severe SAC and PAC cases, such as FML and Lotemax.  FML has been shown to be effective when used in combination with olapatadine when used for a short 1 week course. Lotemax can also be used for short-term treatment, however care needs to be taken in case of an IOP response.

FML has been shown to be effective when used in combination with olapatadine when used for a short 1 week course. Lotemax can also be used for short-term treatment, however care needs to be taken in case of an IOP response.

Stronger preparations such as Prednisilone and Dexamethasone can be used VKC and AKC however this a clinical balancing act between aiming to reduce inflammation while not augmenting any keratitis. This type of treatment is usually delivered by an ophthalmologist, given the risks involved. These patients will often be on a combination of treatments from these various groups, along with topical ocular lubricants.

General approach to patient management

Careful patient assessment, with a clear history and examination to arrive at a diagnosis is crucial. In any cases where something more serious such as VKC or AKC is suspected, gaining an opinion from ophthalmology is perhaps the best approach particularly if there is evidence of limbal or corneal disease.

A lot of SAC and PAC cases however can be and are managed successfully in practice. If the causative agent can be identified, this is really useful so you can help the patient consider ways in which to limit exposure to the allergen involved. Think of the list of non-pharmacological measures that can be employed and which ones may be applicable in the situation.

When medications are required, consider what you are aiming to achieve. If you are aiming to reduce signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction that is already underway, then an anti-histamine may be the most useful means of bringing these symptoms under control. If a patient is aiming to pre-empt an allergic episode, especially in SAC, then a mast-cell stabiliser might be the best option.

Consider a combination if both of these aims would be desirable. If the patient has nose and throat symptoms then an oral anti-histamine might be helpful.

Help and advice can always be sought from optometry, pharmacy and GP colleagues in cases which aren’t being controlled so well, and as discussed previously, ophthalmology referral in VKC and AKC cases.

Useful information can be found at various sources:

College of Optometrists Clinical Management Guidelines

As always I hope this article has provided some useful information and guidance – thanks for reading and please check out any of the other articles and resources on the website!

Stan